The Palaszczuk Government breached its own self-imposed fiscal principles and had to introduce new weaker principles in 2021. The Queensland Government, now headed by Premier Miles but with the same Treasurer, is at risk of breaching two of its revised fiscal principles in coming years.

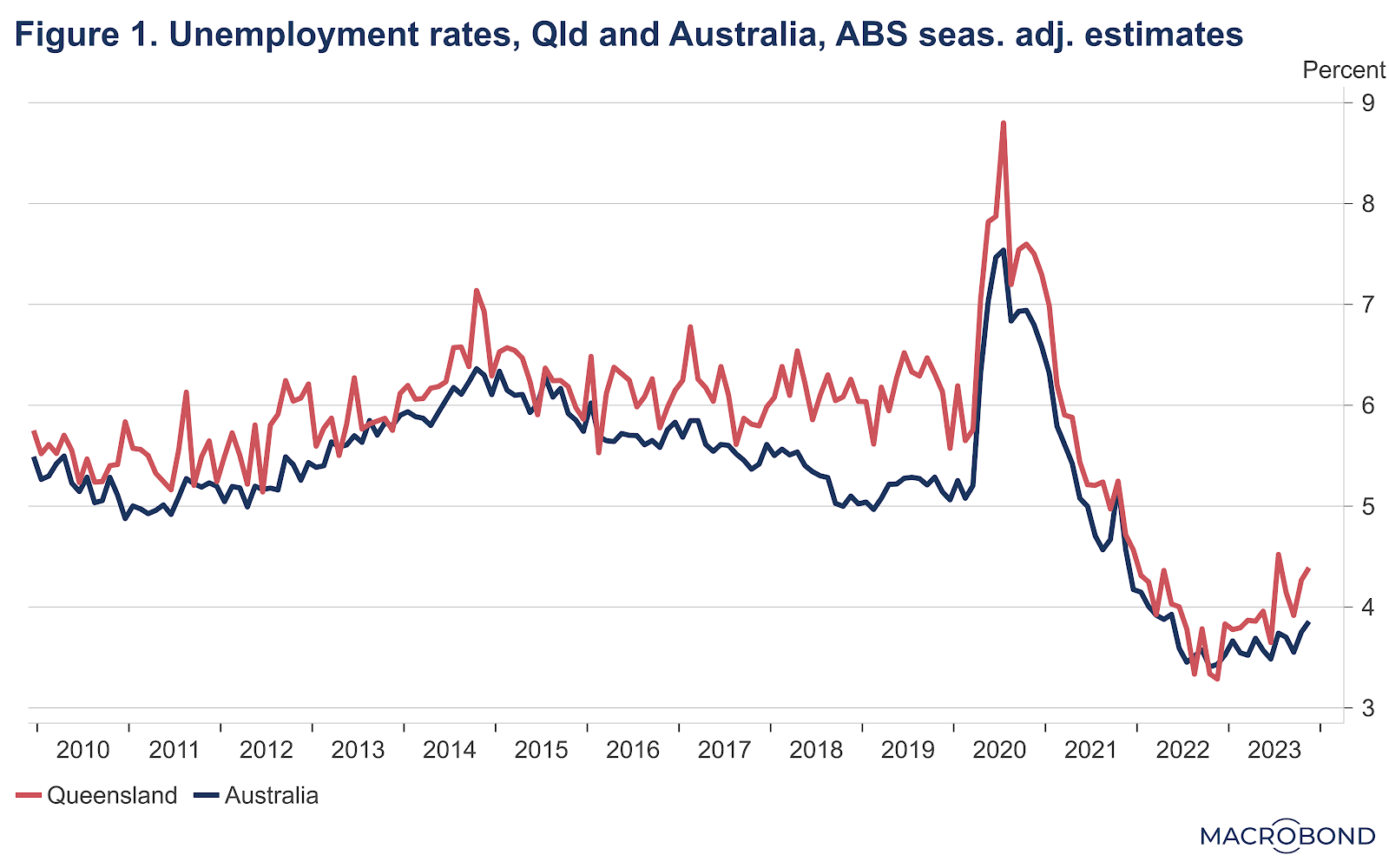

Introduction

The Palaszczuk Government is now history, but its successor, the Miles Government, has to live with decisions made during Palaszczuk’s reign. Those decisions, particularly its failure to abide by its own fiscal principles, now limit the ability of the Miles Government to respond to various crises, owing to the ever-growing public debt interest bill, which is doubling from nearly $2 billion in 2023-24 to nearly $4 billion in 2026-27. The Treasury has to pay the bondholders first, and this money cannot be used to address health, housing, or youth justice crises.

In the mid-2000s, just before the Beattie and Bligh Governments spent up big in response to various energy, water, and health crises, annual interest payments were around $200 million or $350 million in today’s dollars. Relative to revenue, in the early 2000s, interest payments were only 0.6% of revenue, compared with 2.3% in 2023-24 and a projected 4.5% in 2026-27. In this way, government debt reduces the government’s flexibility in responding to community needs.

Performance against its original fiscal principles

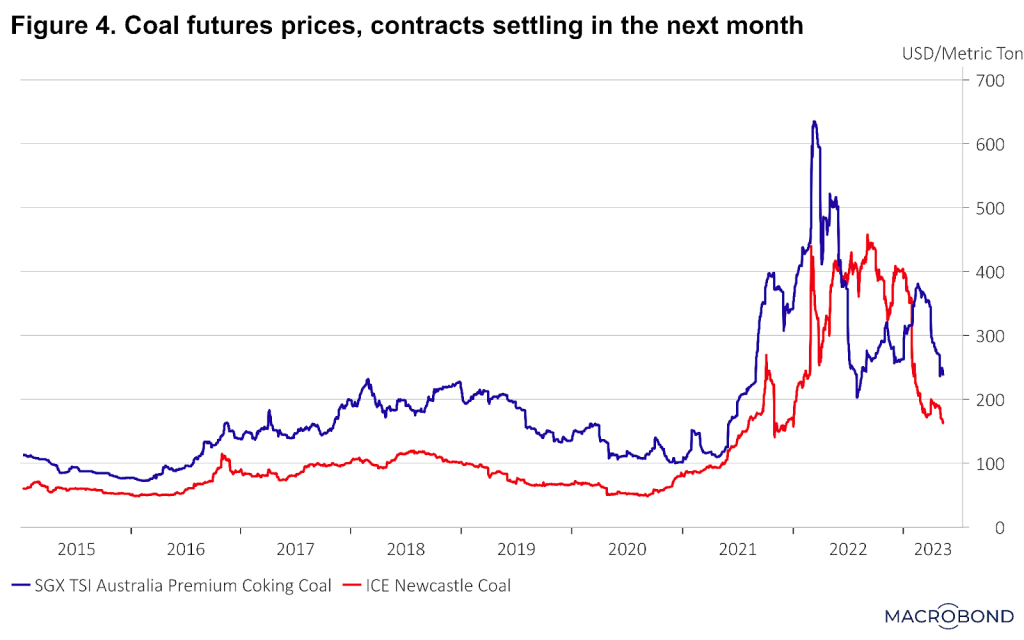

Coming into office in February 2015, the Palaszczuk Government had originally aimed to reduce debt, specifically the general government debt-to-revenue ratio, but it gave up after it proved too hard. It made some early gains, largely by shifting a few billion dollars of debt onto state-owned energy businesses. And later, it benefited from the surge in coal prices since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. However, it could not arrest the trend toward higher debt. General government debt to revenue is projected to reach 111% by 2026-27 (Figure 1). This compares with around 70% in 2015-16, the first full financial year of the Palaszczuk Government. Net debt (i.e. debt less liquid assets such as those managed by QIC) is projected to reach 54% of revenue by 2025-26 compared with only around 1% of revenue in 2015-16. The Government is right these debt figures are much better than figures for NSW and Victoria, but it cannot deny that it has set Queensland on a trajectory of ever-increasing debt.

Figure 1. Queensland General Government gross and net debt to revenue ratios, %

Source: Queensland Budget Papers.

The Palaszczuk Government failed to meet three original fiscal principles (Table 1). It was failing in its debt management principle even before the pandemic. For the other two failed principles, it could legitimately blame the pandemic.

Table 1. Palaszczuk Government performance against original principles

| Principle | Assessment |

| 1. Target ongoing reductions in Queensland’s relative debt burden, as measured by the General Government debt to revenue ratio. | Failed even prior to the pandemic. The debt to revenue ratio was already increasing over the forward estimates prepared in 2019. |

| 2. Target net operating surpluses that ensure any new capital investment in the General Government Sector is funded primarily through recurrent revenues rather than borrowing. | Failed during the pandemic, but that was understandable, given the economic shock and the necessity of a fiscal response to some extent. |

| 3. The capital program will be managed to ensure a consistent flow of works to support jobs and the economy and reduce the risk of backlogs emerging. | No objective way of evaluating performance against this principle. |

| 4. Maintain competitive taxation by ensuring that General Government Sector own-source revenue remains at or below 8.5% of nominal gross state product, on average, across the forward estimates. | The Government met this principle over the period it was in place. However, it could no longer keep it in the 2021-22 Budget due to soaring royalty revenue (e.g. own-source revenue was over 10% of GSP in 2022-23). |

| 5. Target full funding of long-term liabilities such as superannuation and WorkCover in accordance with actuarial advice. | Met. |

| 6. Maintain a sustainable public service by ensuring that overall growth in full–time equivalent (FTE) employees, on average over the forward estimates, does not exceed population growth [introduced in 2016-17]. | Failed during the pandemic. |

Source: Queensland Budget Papers and my assessment.

The biggest failure of the Palaszczuk Government was its failure to keep its principle regarding debt, even before the pandemic. The government failed to meet its first fiscal principle to “Target ongoing reductions in Queensland’s relative debt burden, as measured by the general government debt to revenue ratio” before the pandemic. The 2019-20 Mid-Year Fiscal and Economic Review published in December 2019 projected (on p. 22) the General Government debt to revenue ratio to increase from 54% in 2018-19 to 78% in 2022-23.

The Government could no longer credibly target “ongoing reductions in Queensland’s relative debt burden, as measured by the General Government debt to revenue ratio”. In its revised fiscal principles, discussed in the next section, it set what it may see as the much easier target of the stabilisation of net debt to revenue in the medium term and a reduction in net debt to revenue over the long term, presumably over 10 years or more–i.e. when it would no longer likely be in government and would not be held accountable.

Furthermore, the Government had to abandon its public service growth principle, which it had breached and did not want to be constrained by in the future. In its last Budget using the previous principles (i.e. 2020-21), the Government noted (on p. 101): “The overall average annual growth rate over 2019-20 to 2023-24, based on current estimates, is 1.83%. This compares to an estimated Queensland population growth of 1¼ % annually.” Arguably, this breach of the principle was related to the slowing of population growth during the pandemic and the need to hire frontline health workers.

Incidentally, since March 2015, Queensland public service full-time equivalent (FTE) numbers have increased by 22% compared with growth in Queensland’s population of 14% (Figure 2). Of course, the current Government would argue the difference is due largely to it having to restore public service numbers after the Newman Government.

Figure 2. Queensland Government Public Service FTE numbers

Source: Queensland government workforce statistics, various issues. Note: data for some quarters have been interpolated given the relevant agency does not make reports for quarters prior to September 2019 available online, and they are available by request only. The data prior to September 2017 are from the author’s records and were used in his book “Beautiful One Day, Broke the Next.”

During the pandemic, the Palaszczuk Government could, temporarily, no longer target net operating surpluses or funding capital works largely with operating cash surpluses. However, that was understandable, given the economic shock. In the 2020-21 Budget (Paper 2, p. 16), the Government noted: “The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in some of Queensland’s fiscal principles not being met, and appropriate revisions will be considered ahead of the 2021-22 Budget.”

Finally, the Government had to modify the principle of keeping its own source revenue below 8.5% of GSP because of surging royalty revenues. This principle could have been better designed in the first place, and the new principle of keeping Queensland taxation per capita below the Australian average is arguably superior. This is a principle that Queensland Governments have easily met.

Performance against current fiscal principles

After revising its fiscal principles in 2021-22, because it failed to abide by its previous principles, the current Queensland Labor Government now appears at risk of failing on its revised debt and capital funding principles in future Budgets (Table 2). If it does not slow down the increase in net debt, it will arguably breach its new net debt stabilisation principle. Also, it needs larger net operating surpluses in future to meet its capital funding principle.

Table 2. Palaszczuk Government performance against 2021-22 principles

| Principle | Assessment |

| 1. Stabilise the General Government Sector net debt to revenue ratio at sustainable levels in the medium term, and target reductions in the net debt to revenue ratio in the long term. | Arguably the Government is at risk of breaching this. In the 2023-24 Budget (Paper 2, pp. 55-57), it argues the 54-55% figure in 2026-27 is “sustainable”, but we need to see its projections beyond 2026-27 as the trajectory so far is not encouraging (Figure 1). It may not end up stabilising the ratio at a sustainable level.NB. The Government does not define medium term anywhere, but it should refer to a period of around five years but less than ten years. |

| 2. Ensure that the average annual growth in General Government Sector expenditure in the medium term is below the average annual growth in General Government Sector revenue to deliver fiscally sustainable operating surpluses. | Technically, the Government is breaching this principle, but this is because elevated royalty revenues are falling. From 2022-23 to 2026-27, revenue will fall an average of 0.6% per annum while expenses will increase 3.6% on average. The Government can be excused from temporarily breaching this principle because it relates to the expected moderation of royalty revenue. As the government argues, if royalties are excluded, it meets this principle. |

| 3. Target continual improvements in net operating surpluses to ensure that, in the medium term, net cash flows from investments in non-financial assets (capital) will be funded primarily from net cash inflows from operating activities. The capital program will focus on supporting a productive economy, jobs, and ensuring a pipeline of infrastructure that responds to population growth. | There are modest improvements in the net operating balance over the forward estimates, from a deficit of $138 million in 2023-24 to a surplus of $621 million (or 0.1% of GSP) in 2026-27.But it would be hard for the Government to argue it is “primarily” funding capital spending with net operating cash flows. Chart 12 of the mid-year Budget Update for 2023-24 shows a 35% contribution in 2023-24, increasing to 47% contribution by 2026-27, whereas this should arguably be over 50% to qualify as “primarily”. The Government claims it meets the principle by calculating the contribution over five years (average of 66%) and including the big surplus year of 2022-23. But over the budget year and forward estimates (2023-24 to 2026-27), the average is only 39%. |

| 4. Maintain competitive taxation by ensuring that, on a per capita basis, Queensland has lower taxation than the average of other states. | Met. No risk of not meeting this principle. |

| 5. Target the full funding of long-term liabilities such as superannuation and workers’ compensation in accordance with actuarial advice. | Met. No risk of not meeting this principle, unless the Government withdraws further funds from schemes. |

Source: Queensland Budget Papers and my assessment.

In future Budgets, the Government is at significant risk of failing to meet its new debt principle, even though it is much weaker than the old principle. Queensland General Government net debt to revenue is currently projected to increase over the forward estimates (see Figure 1). Arguably, the government must take seriously its goal of stabilising net debt to revenue. It also needs to do better against its net operating balance and capital funding principle (principle 3), as discussed in Table 2.

Conclusion

Like the Bligh Government, the Palaszczuk Government, now the Miles Government, rejected the approach of sound public finance established by Treasurers of previous post-war state governments, including Keith DeLacy and Terry Mackenroth on the Labor side and Gordon Chalk and Tim Nicholls on the conservative side. The Government is now paying the consequences for its lack of fiscal discipline, as it needs to fund a sharply rising public debt interest bill while managing multiple crises in health, housing, and youth crime.

Please feel free to comment below. Alternatively, you can email comments, questions, suggestions, or hot tips to contact@queenslandeconomywatch.com. Also, please check out my Economics Explored podcast, which has a new episode each week.