On Thursday evening, I joined John Humphreys of the Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance and Professor Chris Berg of RMIT University for an ATA livestream discussion on productivity (see Productivity ideas with Chris Berg). One of the most interesting parts of the conversation was on artificial intelligence (AI), which I’ve repurposed for my latest Economics Explored podcast episode.

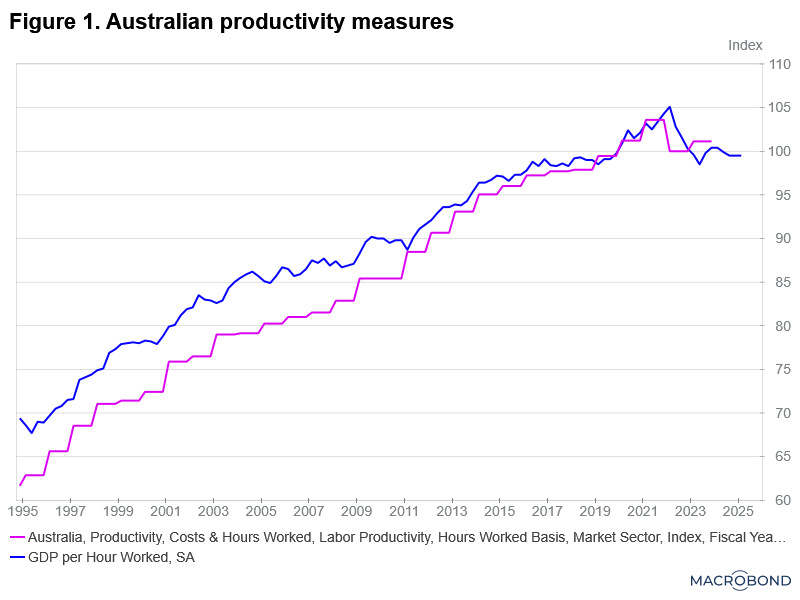

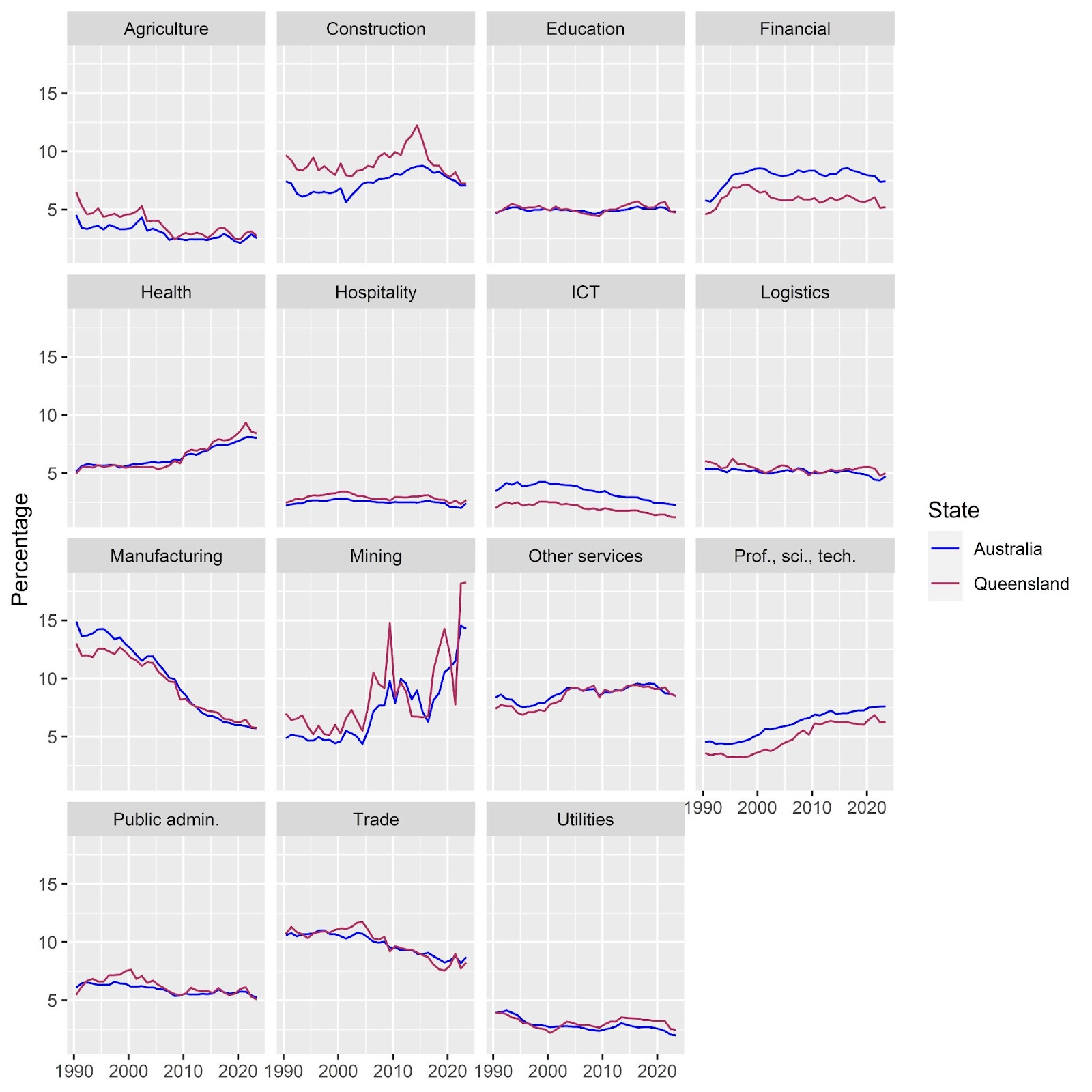

Chris argues that AI could be the greatest productivity-enhancing technology since the Industrial Revolution. He noted studies showing that white-collar workers using tools like ChatGPT can already achieve productivity gains of 17–45%. If that holds true at scale, it would be transformational for economies like Australia’s, where sluggish productivity growth has become a major concern.

Thankfully, the Albanese Government has so far resisted pressure—particularly from unions and lobby groups—to introduce heavy AI regulation. Instead, it has adopted a wait-and-see approach, unlike Europe, where regulation is already slowing the rollout of new AI tools. Chris welcomed this hands-off stance, seeing it as giving Australia a chance to capture the benefits of AI adoption more quickly.

One of the more provocative points from Chris was his description of AI as providing “effectively infinite intelligence.” I challenged this idea, suggesting that while AI can synthesise vast amounts of existing knowledge, true intelligence involves solving new problems. Nonetheless, I share his view that AI represents an extraordinary advance.

We also discussed who wins and who loses in an AI-driven economy. Contrary to the usual automation story, Chris argued that it may be highly educated professionals who face more disruption than low-skilled workers, since AI excels at writing, analysis, and other cognitive tasks. At the same time, concerns remain about those unable to effectively use the technology being left behind.

Beyond work, AI raises broader social and ethical questions. We talked about AI companions, therapeutic uses (such as support for people on the autism spectrum), and risks of parasocial relationships or loneliness. The potential benefits are real, but so are the challenges.

Finally, one of the more imaginative suggestions was that low-skilled work in developed economies could in future be done by humanoid robots remotely operated from overseas. This would create a new twist on globalisation and migration policy—an idea worth thinking through further.

Overall, it was a fascinating conversation, with plenty of optimism from Chris about AI’s productivity potential, tempered by my own caution about the risks and unknowns.

If you’d like to watch the whole conversation with Chris, you can check it out on the ATA YouTube channel. In addition to discussing AI, we also discuss the Economic Reform Roundtable.

Please feel free to comment below. Alternatively, you can email comments, questions, suggestions, or hot tips to contact@queenslandeconomywatch.com.